Why does admixture create LD between unlinked loci?

Admixture generates linkage disequilibrium between loci, even those that are unlinked (i.e. segregate independently or reside on different chromosomes). A lot of my PhD was spent thinking about admixture and admixture LD gave me some grief. Recently I went back to some old notes on the topic to try and explain this to my students and I figured I’d share them in case others find them helpful.

The intuition behind admixture LD

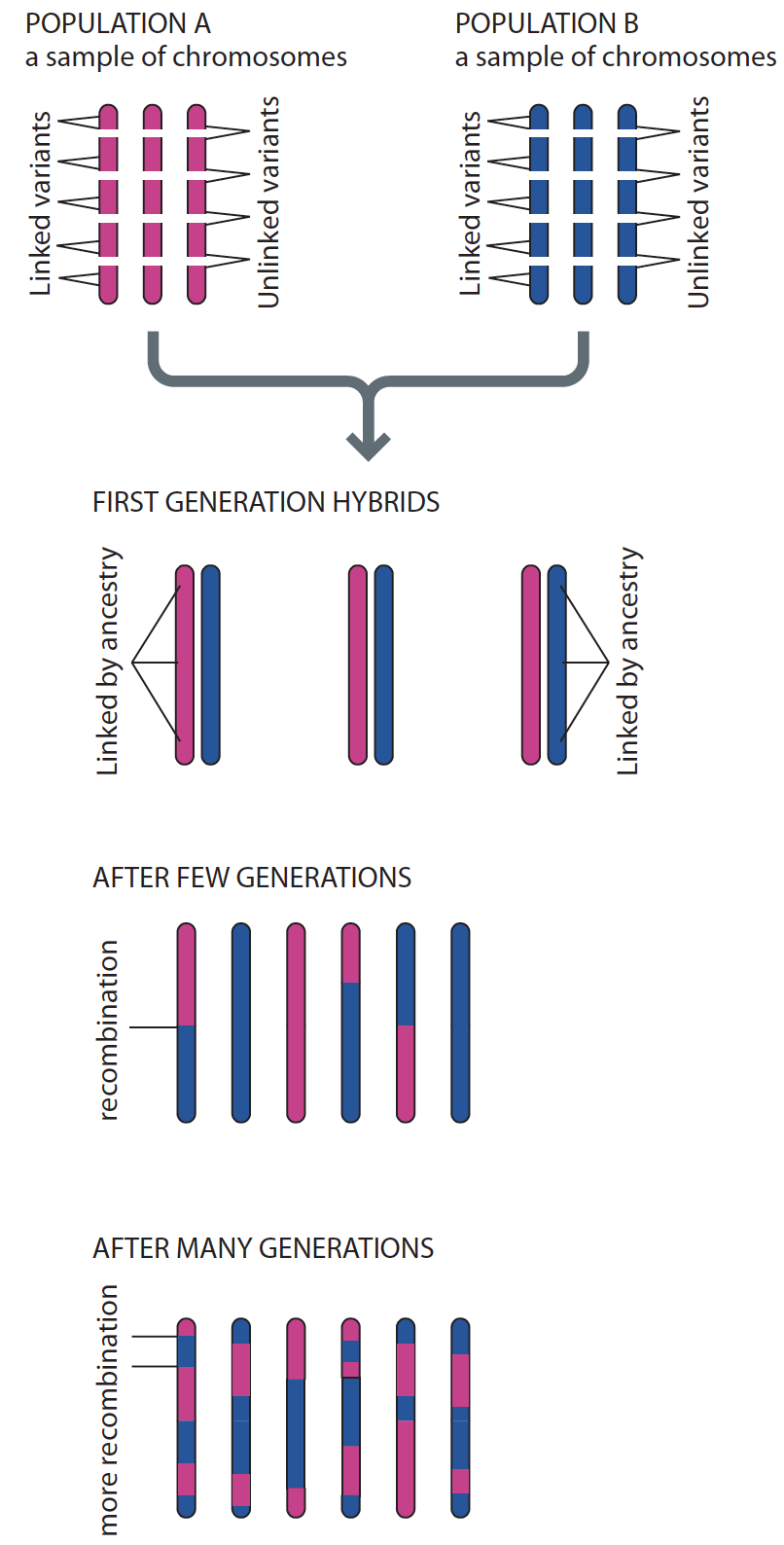

For an intuitive explanation, I actually quite like the illustration in Human Evolutionary Genetics 1. Let’s consider a simple model of admixture between two populations (red and blue), which have been reproductively isolated (Fig. 1). In the first generation, all individuals will have one blue and one red chromosome. Now let’s say you sampled a single chromosome and determined it’s ancestry (red or blue). Because chromosomes can either be entirely red or entirely blue, you will immediately know the ancestry of all loci across the genome with absoulte certainty, even for loci on different chromosomes (Fig. 1). In other words, the ancestry across loci are complettely correlated in the admixed population. This correlation in known as admixture LD.

Fig. 1: Admixture generates LD between loci. Figure from Human Evolutionary Genetics (2nd Ed).

Fig. 1: Admixture generates LD between loci. Figure from Human Evolutionary Genetics (2nd Ed).

Problem is, we can’t know the ancestry at a locus. Chromosomes are not painted red or blue (or which population they come from). What we can find out are the genotypes (by genotyping/sequencing). Does admixture induce correlations between genotypes at unlinked loci? Yes, but this correlation depends on a number of things and to develop a more nuanced (and quantitative) understanding, we need to do some math.

Factors affecting admixture LD

Let there be two (randomly mating) populations that have been reproductively isolated for enough time for there to be systematic frequency differences between them. Denote

Statistically speaking, LD is a measure of the covariance in genotypes between two loci. For population 1, the covariance,

Now, imagine that there is an admixture event where individuals from populations 1 and 2 are put together in a single population in proportions of

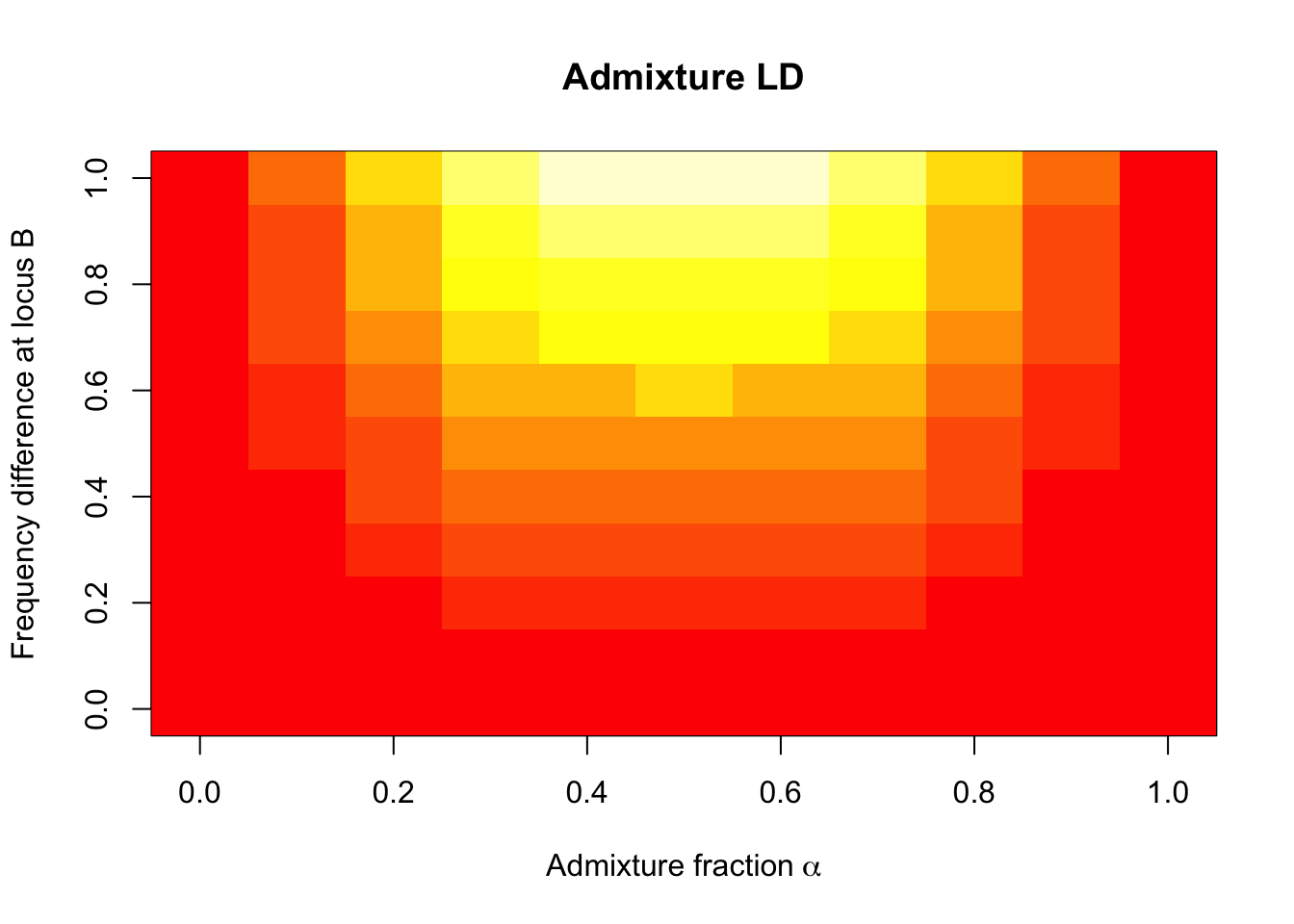

This shows that the admixture LD between the genotypes at two loci depends on two things: (i) the product of the allele frequency difference between the two populations

#create matrix to store D

dmat = matrix(NA, nrow = 11, ncol = 11)

alpha = seq(0, 1, 0.1) # range of values of admixture fraction

fdiff = seq(0, 1, 0.1) # range of values of frequency difference at locus A. assume difference at locus B is 1.

for(i in 1:11){

for(j in 1:11){

dmat[i,j] = alpha[i]*(1 - alpha[i]) * 1 * fdiff[j]

}

}

image(dmat, main = "Admixture LD", col = heat.colors(12),

xlab = bquote("Admixture fraction"~alpha), ylab = "Frequency difference at locus B")

We can tell that there will be no LD between unlinked loci (i.e.

Admixture LD is maximized (bright yellow region) when two conditions are met: (i) when

Admixture LD decays pretty rapidly with random mating

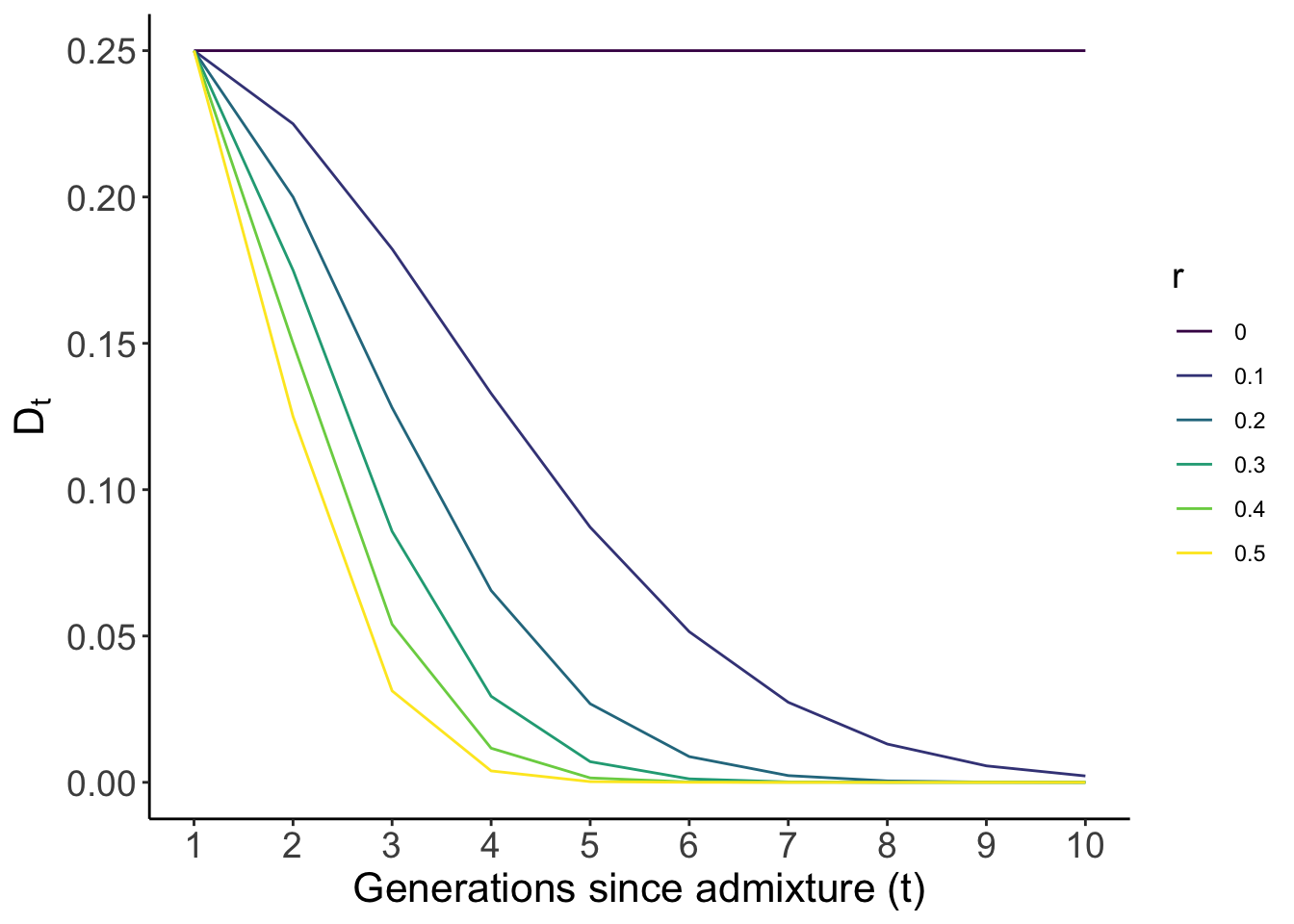

So far we’ve only considered LD right after admixture. Admixture LD between unlinked loci decays pretty rapidly after admixture in a randomly mating population due to recombination between loci and independent assortment (see Fig. 1 again). Let’s denote admixture LD in generation

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library(ggplot2))

#range of values of r (recombination fraction)

r = seq(0, 0.5, 0.1)

dtmat = matrix(NA, nrow = 6, ncol = 10) # matrix to store values of dt

#max possible value of D0 is when alpha = 0.5 and when freq diff is 1.

#this leads to a max value of 0.25

for(i in 1:6){

dt = 0.25

for(j in 1:10){

dtmat[i,j] = dt

dt = dt*(1 -r[i])^j

}

}

dtmat = reshape2::melt(dtmat)

colnames(dtmat) = c("r","g","Dt")

dtmat$r = (dtmat$r - 1)/10

ggplot(dtmat,

aes(g, Dt, group = r,

color = as.factor(r)))+

geom_line()+

theme_classic()+

theme(axis.text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14))+

scale_color_viridis_d()+

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1:10))+

labs(x = "Generations since admixture (t)",

y = bquote(D[t]),

color = "r")

As you can see,

LD between unlinked loci can also be generated due to population structure or assortative mating in the population (non-random mating broadly). Thus, admixture LD is a special instance of a more general phenomenon whereby demographic processes (e.g. population structure and assortative mating) can induce correlations across the genome. The correlations between unlinked loci that arise due to population structure and admixture is sometimes called the multi-locus Wahlund effect. Sometimes people call this type of LD gametic phase disequilibrium (how’s that for a mouthful) to distinguish it from LD due to physical linkage.

Fig. 14.13, page 461 of Human Evolutionary Genetics, 2nd edition. I this book is a fantastic resource if you want a bird’s eye view of the breadth of topics in human genetics. It also provides important references, which are really handy if you wanted to find papers for more in-depth study.↩︎

From the definition of covariance.

This is pretty straightforward but I always like to explicitly show the statistical statements underlying such expressions. Let’s denote

The frequency differences are themselves a function of the

Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics (4th Edition). vol. 12. 1996.↩︎